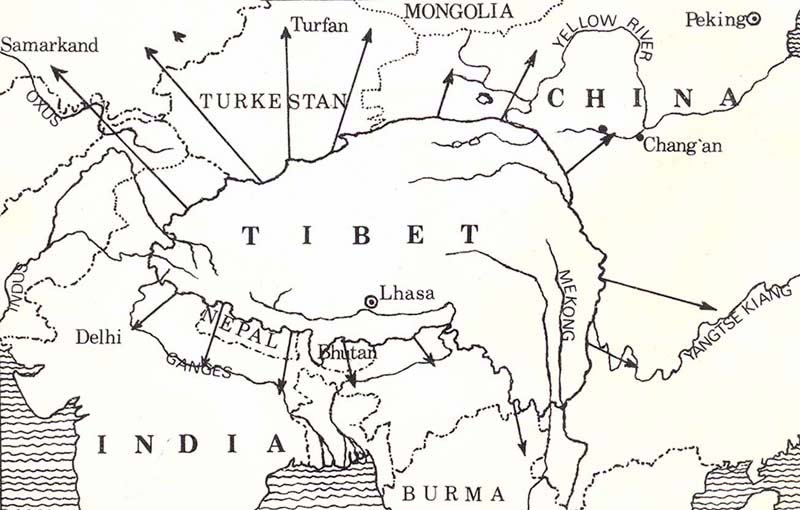

Tibetan armies ventured far beyond the borders of Tibet during the time of the Empire.

In the rugged mountains of what is present-day Afghanistan, a long line of horsemen wound their way across the barren hillside. Below them, snaking across the plain, lay the glittering waters of the River Oxus- today’s border between Russia and Afghanistan. One glance was enough to tell that these were fierce warriors, hardened by many years of war. Trained in the wild mountains of Tibet, these soldiers were expert horsemen, skilled in the use of the bow and the sword. Tough sports and competitions had prepared them for battle. Their leaders, it is said, were able to race the wild ass and wrestle with the wild yak.

Slowly, the horsemen descended to the plain and began to cross the River Oxus. No wonder the Arab leaders shook in their palaces. The Tibetan’s fame had already spread far and wide. The Emperor of China, it was said, trembled when he heard of the approach of the terrible Tibetan horsemen. Now they were advancing into Arab territory as well. We have some idea of how far these Tibetan armies reached, because there is a lake many miles to the north of the River Oxus which was named Al-Tubbat, which means “Little Tibetan Lake.” Some writers report that a Tibetan army even battered the walls of Samarkand- deep in the heart of Arab lands.

Songtsen Gampo’s successors all continued the expansion of the Tibetan Empire. They also gave support to the Buddhist religion, as we shall see. Tibetan armies continually fought with the Chinese on their eastern frontier. In the reign of Mangsong Mangtsen (649-676), the Chinese Emperor dismissed so many of his generals for losing battles that he soon had no one left to lead his armies! So powerful did the Tibetans become, that they forced the Chinese to pay them a yearly tribute of 50,000 rolls of silk. When the Chinese Emperor, Wang Peng Wang, refused to pay in 763, the armies of the great Tresong Detsen (755-797) advanced into China itself. The Emperor and his ministers fled in the terror, and the Tibetans occupied the Chinese capital of Chang’an. For a short time, they set up their own candidate as the new Emperor of China. The successes of Tresong Detsen’s wars with China are written down on a stone pillar in Lhasa.

In 783, a peace treaty was agreed between Tibet and China. This established the boundaries between the two counties and gave Tibet control of most of the border provinces in the east. The treaty was written down on a stone pillar in the village of Shol below the Potala, where it still exists today. A further treaty between the two countries was agreed on in 821. The terms were virtually the same as the treaty of 783, and this time they were carved on three stone pillars. One was erected outside the Chinese Emperor’s palace, one on the border between the two countries, and one in Lhasa. The significance of both of these peace treaties is that they are clearly arguments between two equal and independent countries.